Masculine Immunotherapy

“You might want to prepare yourself for chemotherapy,” I heard the doctor say as I sat stunned trying to process the news. Chemotherapy? Cancer? Surgery? How can this be happening? I thought of my family, my wife, my daughters, and my grandchildren and of course, I thought of my own father and his battle with cancer.

This was the opening scene in my own cancer drama a couple of years ago. The first step was major surgery then, pending a pathology report, I was told to prepare for one, possibly multiple rounds of chemotherapy. In the days and weeks before the scheduled surgery, I battled all the emotions one can think of. It was an experience I wish upon nobody.

Finally, my operation was scheduled and the procedure went smoothly. When I awoke, it was with great relief that the doctors reported that the tests were negative. I was cancer-free. My particular affliction was intense and full of anxiety, but mercifully short-lived and quickly resolved. I thank God I didn’t have to undergo Chemotherapy.

The entire experience and process did, however, get me thinking about my life and our work at Epik Project to end the demand for exploitation. As I pondered, I began to correlate our work with the nature of cancer treatment.

Chemotherapy targets bad, cancer-causing cells like a shotgun blast. Shotgun blasts, as we know are expansive and that imprecision means there is always collateral damage to the surrounding organs and tissue. However, that damage is considered acceptable in the hopes that those areas will eventually recover. Even though oncologists know this, the risk/reward calculations are always difficult and fraught with levels of uncertainty. You could call chemo the lesser of two evils but, for the patient enduring the treatment, it still feels evil. Nevertheless, chemo is often the best hope; sometimes, it is the only hope. But sometimes there’s a better way.

We’ve been fighting sex trafficking for decades like oncologists treat cancer with chemotherapy. In response to the malignancy of sexual exploitation, we target the bad “cells”; the pimps, traffickers, or maybe the buyers. We inject a dose of punitive policies into the societal bloodstream at the local, state, and federal levels in an effort to arrest the disease.

However, these policy prescriptions, like chemo, often have severe side effects. The most significant of which is the further traumatization of victims; the collateral damage that happens when they get swept up in a process that can often lack adequate trauma-informed training and resources thereby causing further damage to the very people we’re trying to help. Marriages and families are also part of that collateral damage calculation.

Another more nuanced side effect is ambivalence. As long as we see cops busting bad guys (i.e. the “bad cells”) like pimps and buyers, we (communities and individuals) can be lulled into complacency. As long as somebody is getting arrested, it looks like the treatment is working.

Epik Project has been actively engaged in this ecosystem for more than a decade and we’ve intercepted nearly 300k online attempts to buy sex. I can tell you based on real-time, front-line intelligence that even through dramatic economic downturns, pandemics, and other natural and financial disasters this masculine malignancy is remarkably durable.

“Ironically, it’s top law enforcement leaders who have been repeatedly saying that we can’t arrest our way out of this problem because, at the root, sexual exploitation is a systemic problem that requires a systemic solution.”

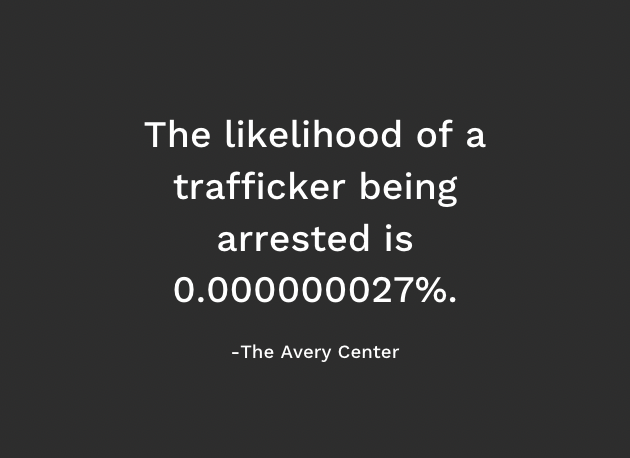

Yes, buyers are being arrested every day, but that doesn’t mean the problem is being taken care of. Ironically, it’s top law enforcement leaders who have been repeatedly saying that we can’t arrest our way out of this problem because, at the root, sexual exploitation is a systemic problem that requires a systemic solution. We can’t simply ramp up the dosage in this chemotherapeutic scenario and hope to provide actual healing for everyone harmed by this sickness.

By definition, a chemotherapeutic approach to sex trafficking will always have a limited impact. Targeting the bad cells of pimps and johns in the cultural bloodstream can have a positive effect to be sure, but ultimately all it does is keep the “disease” of exploitation at bay. The small number of sex buyers who actually get arrested represents a much larger population who never get caught or face any kind of accountability. While the threat of arrest is a valid deterrent, it hasn’t proven effective in slowing the progression of this unique form of masculine malignancy.

Case-in-point: the online ecosystem that facilitates sex trafficking is full of “Yelp”-like review sites that offer robust and detailed peer-to-peer consumer advice; conversations about how to not only buy sex in an increasingly complex and distributed marketplace but also how to avoid getting caught while shopping. Like mutated cancer cells, the sex-buying population has evolved and adapted to our chemotherapeutic strategies.

In the face of this diagnosis, legislators respond to the prevailing winds of public opinion to form a policy response. More and more it seems this response acquiesces to the notion of abandoning the whole toxic system to the free market; allowing the commercial sex industry (and the sex trafficking that inevitably results) to flourish by actual or de facto full decriminalization. Ostensibly, this kind of response is supposed to reduce any unintended harm to those at risk of exploitation.

Advocates call it “harm reduction” but a policy shift like this makes as much sense as treating a cancer diagnosis with a bandaid. Why settle for simply reducing harm when eradicating the very source of that harm altogether might actually be possible? Decriminalization is akin to palliative or hospice care; the “patient” (in this case male culture) is terminal, so let’s lessen the pain. But chemo is better than mere pain management; are we really willing to capitulate to urban legends like “boys-will-be-boys,” or “that’s just the way men are…” or do we dare to hope for more from men? I for one am not ready to give up on the healing and health of men that easily. I believe there’s another way.

One of the most promising developments in our lifetime for the treatment of cancer is immunotherapy. While chemo acts directly on “fast-growing” cells and is active as long as the drug is in the person, immunotherapy works at a different level. It’s designed to work with the body’s own built-in immune system, enabling it to do what it was created to do; rid the body of any foreign “threat” to health and flourishing. Immunotherapy strengthens the body’s natural immune response system to identify and ward off any threats. This response system is key, and we’ve only recently discovered just how much power it contains.

In our example then, as long as cops are running undercover missions targeting bad cells of sex buyers and pimps - a chemotherapeutic approach - there will be a limited effect, but when the medication wears off - when the chemo is out of the system - when the mission is over, the cops go home, the DA refuses to prosecute exploiters using the laws already on the books, buyers will keep buying, pimps will keep selling and the most vulnerable will keep being exploited. But with a larger, sustained strategy in place to reinforce a robust masculine immune response system, in other words, if widespread, healthy communities of men were thriving, the chance of malignant exploitation surviving in proximity to those communities would be dramatically reduced.

Four voices have shaped my thinking about this. The first is researcher Mike Shively. For more than 20 years he’s been diligently examining the ecosystem that drives sex trafficking and has said on more than one occasion that we don’t need any more laws to deal with this issue, we need to use the ones already on the books. In other words, we have what we need to continue a targeted chemotherapeutic approach. Second, Gail Dines has also been researching the effects of pornography and its clear intersection with sex trafficking and she told me years ago that this issue is a problem in the hearts of men (a systemic problem) and until we deal with it that way, (a systemic response) we’re never going to make lasting changes. Third, Andrea Heinz, both a survivor of the sex trade and researcher, continually points to the need for healing within the wider masculine culture (again a systemic response). And finally, Curtis Miller, community psychologist and Epik Project partner has taught us that ultimately, cultural (systemic) change happens at the speed of relationships and relationships happen at the speed of trust. This is a job for good men everywhere.

“What’s the worst that would happen if large numbers of men began to flourish in healthy, life-giving ways all across the country?”

Even if I’m wrong, what’s the worst that would happen if large numbers of men began to flourish in healthy, life-giving ways all across the country? Furthermore, exploring the potential of an idea like this wouldn’t require a massive increase in law enforcement resources or a bunch of new laws. Those structures are still valid in the same way chemotherapy is still a valid treatment for cancer. Targeted, punitive responses to the worst perpetrators of exploitation remain necessary, but they needn’t be the first or only response to this evil. We must now turn our attention to nurturing life-giving systems that can exert a masculine immune response to the cultural carcinogen of sexual exploitation in all its toxic forms. We have to invest in building communities of healthy men at a massive scale; I’m talking about a cultural commitment to and sustained investment in the development of a global masculine immunotherapeutic approach to sexual exploitation.

Sexual exploitation, and by extension sex trafficking, flourish in our culture because of endemic, male sexual entitlement. Boys become men in a world that has so thoroughly normalized hypersexuality that it becomes like the air we breathe. That reality along with the metastasized loneliness and isolation that plague most men creates a perfect storm of toxicity. Raised in a sexually saturated environment and longing for authentic connection, is it any wonder so many men see sexual gratification (whether by coercion, consent, or a paid transaction) as both a birthright and a cure for their loneliness?

After 15 years of work on the front lines of this movement, I firmly believe men both desire and have an enormous capacity for healthy, authentic connections. Our experience of directly engaging with active sex buyers for more than a decade has shown us the depth of that desire, and the lengths to which they’ll go in search of it; even when that search leads in the wrong, devastating direction. But when good, healthy, wise men show up to disrupt that misguided search, when we speak truth in love to men in a moment of extraordinary vulnerability (like when they’re thinking about buying sex), when we offer a different, healthier invitation to connect, the experience is transformative. Though it’s often latent, men have a potent capacity for deep and healthy connection. We were created for it and we can and must do a better job of nurturing it in each other. At this moment in history, we have a profound opportunity to invest in promoting and sustaining communities (systems) of healthy men so that when they’re exposed to carcinogenic threats, a healthy masculine immune response results that can eliminate that threat.

Currently, this kind of masculine immune response system is weak and underdeveloped. Far too few men in our world have had enough exposure to healthy masculine communities, and by that, I don’t mean spaces devoid of female influence. A healthy masculine space is where men feel the freedom to express the full range of their humanity, and we need women to help build these spaces. We cannot become full, healthy men in the absence of the loving influence of women as leaders, mentors, guides, and friends because healthy masculinity is impossible without healthy femininity. Throughout our history as an organization, women have been our strongest advocates and one of the greatest resources to help nurture our flourishing as men.

There’s also something healthy and hopeful emerging in generations of younger men. It seems as if many (by no means all) young men are showing unexpected resistance to some of the more toxic elements of conventional masculine culture. For example, stunted, stoic emotionless responses to life are being replaced by more nuanced, broader, and healthier ones. Recently I watched in admiration as future Hall of Fame NFL star Jason Kelce cried freely on his podcast while talking about his mom, his wife, daughters, and his impending retirement from a game he loves while his future Hall of Fame brother, NFL star Travis looked on in tears.

Not long before that, I stood in a sweaty middle school classroom crammed with more than 70 12-14-year-old boys as they listened respectfully to a senior high school student. He challenged them to advocate for vulnerable people (in this case, the girls in their own school) He talked with passion and clarity about how these young men were in a unique position to advocate for safety and security. He challenged the normalization of objectifying women and told these young men, “Just because it's normal, doesn’t mean it's right.” The sober response from the boys to the high school students' challenge seemed to suggest that perhaps they possessed some sort of acquired resistance to some of the more toxic elements of masculine culture. It's as if sustained exposure had built up a healthy resistance (dare we call it “immunity?”) to that toxicity and they were just waiting for someone or something to call out something better. A healthy masculine immune system will do that…and possibly much much more.